In her 1976 review of Carrie, critic Paulline Kael wrote of director Brian De Palma as having a “sophisticated, absurdist intelligence” and “the wickedest baroque sensibility at large in American movies.” Upon working my way through his films this summer, I too have noticed his style and unique directorial ability. Quite simply, he’s a natural.

I get the sense that De Palma’s material has never quite matched his talent. While his films are good, some quite so, he never made a Godfather, Jaws, or Raging Bull as his some of his contemporaries in the class of the 70s did. My view is of course subjective, as Quentin Tarantino has listed Blow Out as one of his all-time favorite films. Nonetheless, I have found plenty to admire in De Palma’s work, and, with the camera, he has a skill that is hard to ignore.

Brian De Palma on the set of ‘Mission: Impossible’ (1996). Image via Britannica.

My early exposure to Brian De Palma was through Mission: Impossible, Scarface, and The Untouchables. There was something about Mission: Impossible (1996) that felt so alive and visceral to me as a child—even more so than it's sequels that have larger, more complex set-pieces and stunts—and, to this day, I recall the chills that the elevator scene gave me, on a small home TV no less. Unaware of directorial sensibilities at that time, I see upon reflection how a De Palma was able to weave the energy of the camera to meet the potential of the story. Recently re-watching Scarface (1982)—I thought it was okay when I first saw it—I noticed the voice of the camera and its elevation of the material’s inherent melodrama, introducing the artifice of a cinematic world. With The Untouchables (1987), I analyzed a few scenes for a school project as a freshman in high school. Looking back, that was my first time doing film analysis. The production design jumped out to me then, but in two key scenes—the shootout and the opening shaving scene—the evocative nature of the camera left a mark in my memory.

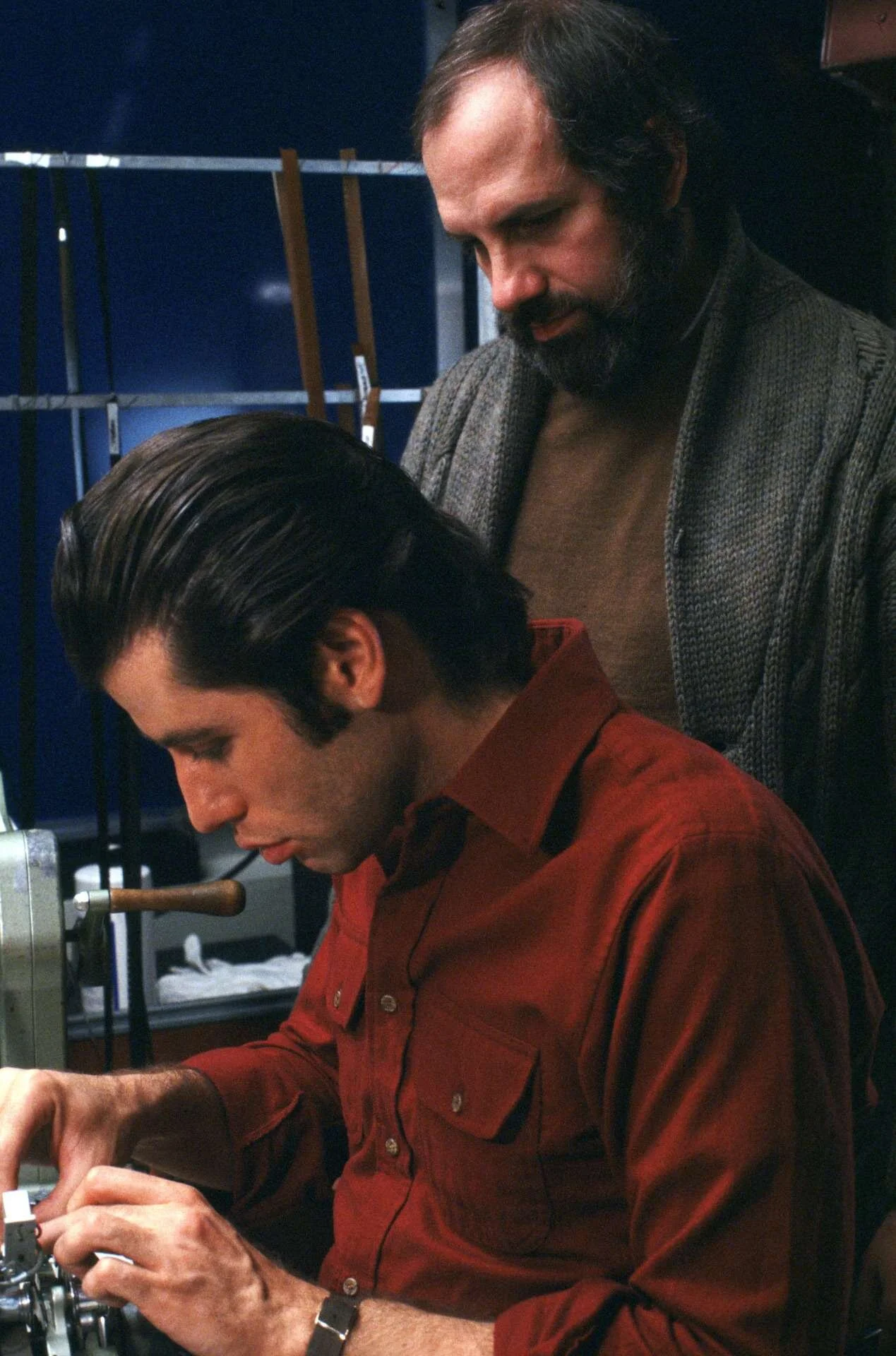

On the set of ‘Blow Out’ (1981). Image via Cinephilia & Beyond.

It is hard to describe with words the techniques of the director and what makes them pop. For one, De Palma uses color alone and in a variety to create both depth and atmosphere. As mentioned with Scarface, his material tends to be melodramatic or pulp in nature, even somewhat farfetched. (I think of, regarding the use of color and visual energy, to Nicholas Ray’s Rebel Without a Cause or Douglas Sirk’s All That Heaven Allows (both 1955). His style suits this heightened reality, and with full embrace De Palma gives his films a fantastical feel. A strong score; use of slow-motion and larger spatial set-pieces; sound design (particularly in Blow Out [1981]); and a willingness to use zoom lenses, split diopter shots, and other techniques that draw attention to the presence of the camera—all elevate the sense of movie magic.

As Kael puts it, with De Palma ”you know you’re being manipulated, but he works in such a literal way and with so much candor that you have the pleasure of observing how he affects your susceptibilities even while you’re going into shock.” His filmmaking is self-aware, alive. De Palma employs the camera as an instrument to speak his artistic voice.

I quite enjoyed Carlito’s Way (1993)—the film was fun and I found myself immersed in the surprising believability of the world. Carrie (1976) too, while feeling very much of its time, provides ninety minutes of sheer thrill and excitement. I look forward to continuing to explore the director’s work. To learn more about Brian De Palma, the 2016 documentary on the filmmaker is a great a place to start (trailer below).

As someone living in 2020, there is something about discovering and rediscovering De Palma’s films that has sparked my own curiosity for the potentials of filmmaking as a medium. His films remind me I still have much to learn.

In an interview with Matt Zoller Seitz, De Palma says: “A movie is a work of art. It either exists and people keep looking at it, or it vanishes. So, I have very little to do with it, and a movie has basically got to find its own way. And many of my movies, people are still looking at 30 or 40 years later, so I guess there’s some value in it, because they’ve existed through the ages.”

I agree to an extent, but Brian De Palma’s films surely still have life because he put a lot of life into them.

- JG

_